One of the unique aspects to U.S. men's national team coach Gregg Berhalter is that his godfather is baseball legend Carl Yastrzemski. Here's how that came to be.

It wasn’t his interest in soccer that left Gregg Berhalter feeling like an athletic outlier while growing up in northern New Jersey. Although it was never the most popular sport, soccer enjoyed a relatively firm foothold there. The impressive list of U.S. national teamers hailing from the Garden State is testament.

The problem was with Berhalter’s other favorite sport, baseball. And it became an issue in the fall of 1981, as the Yankees and Dodgers met in the World Series. He was 8 years old.

“I was the only one in my class rooting for the Dodgers,” said the Bergen County, N.J., native, who was born and raised across the Hudson River from Yankee Stadium. “I was always a Red Sox fan. Trust me, it led to some very interesting conversations with people.”

The future U.S. national team coach wasn’t trying to be a contrarian or an 8-year-old iconoclast. The truth was, he didn’t really have much of a choice in the matter. He may have been raised in Yankee territory, but the Red Sox were in the blood. Boston’s most famous player at that time, Carl Yastrzemski, was (and still is) Berhalter’s cousin and godfather, and his childhood came with a backstage pass to places his classmates couldn’t imagine.

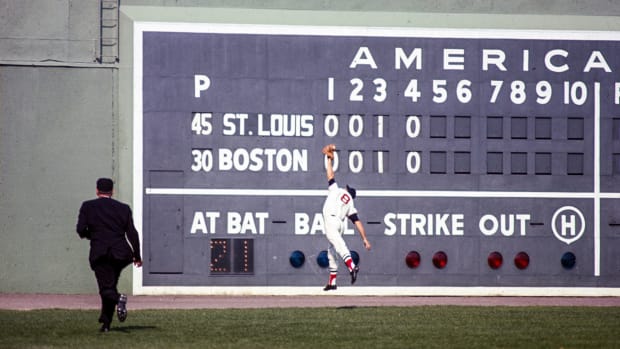

Yastrzemski finally retired in 1983 after a 23-season, Hall-of-Fame career, and Berhalter and his family were there at Fenway Park as the legendary left fielder said goodbye. “Yaz Day” was one of several visits to Boston that Berhalter was able to make as a kid.

“I remember going on the field, being on the field for batting practice, going into the clubhouse after the game—all that stuff,” Berhalter said. “It was great to be around the club house, but just being around Fenway—climbing on the roof and looking for foul balls, just being a Fenway rat.”

There’s still a touch of nonchalance when he talks about it. It was close to normal back then but has become much more special in hindsight.

“You don’t realize when you’re that young. It just becomes natural. You knew how good he was. He hit for the triple crown. Not many people have done that. [At that time], he was an aging baseball player,” Berhalter recalled.

He’s telling this story in early April, shortly after the conclusion of a FIFA international window that never was. Berhalter was supposed to take the USA to Europe for friendlies against Netherlands and Wales. But those games, like every other sporting event, were wiped out by the coronavirus pandemic. So instead of diving into a review of the trip and the matches and training sessions spent with a full squad for the first time in 2020, Berhalter was home in Chicago, answering questions on a far more informal topic.

It’s ironic that in this barren stretch of canceled competitions and closed arenas, we’ve become closer than ever to the people who work and perform there. Over the past few weeks, via Zoom and FaceTime and all kinds of screens, we’ve been invited into the homes of athletes and coaches around the world. We’ve seen where they eat breakfast and watch TV, how they display their memorabilia and how they work out. We’ve met their families

and their pets. We hung out in Wayne Gretzky’s living room while he played NHL 20. We spent three days in Roger Goodell’s basement.And so we’re learning something about the U.S. national team manager, whose official U.S. Soccer bio is full of the information and trivia you’d expect detailing his own playing career and journey as a coach, up until the bit in the last paragraph that reads, “Berhalter is the godson of former Boston Red Sox player and baseball Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski.” It’s a sentence that appears buried and glaring at the same time.

What? How?

This seems like a good time to learn the rest of the story. And like most stories about Carl Yastrzemski, and we assume all old-school baseball players, this one begins on a potato farm.

Yastrzemski was raised on the eastern end of Long Island, N.Y., on his parents’ potato farm. Berhalter’s mother’s family lived nearby.

“My mom’s side of the family are Polish potato farmers from Long Island, and my grandfather’s sister—my mom’s father’s sister—is Yaz’s mom. He’s my second cousin, and he happens to be my godfather,” Berhalter explained.

That upbringing helped shape Yastrzemski as a player, according to both Berhalter and Mike Yastrzemski, Carl’s grandson who’s an outfielder for the San Francisco Giants.

“It even stems further than that to my great grandfather. Everyone said he was the best hitter in our family. They had a family team that played in like a semipro league on Long Island and my grandfather and great grandfather, they hit third and fourth,” Mike Yastrzemski said. “My great grandfather was always a better hitter, but he had to run the potato farm so rarely had the luxury to go play.”

That instilled an approach that caught Berhalter's attention at a young age.

“Polish potato farmers—those guys are tough. My grandfather was a fisherman and a farmer. Their hands were huge. They could do anything, make anything,” Berhalter said. “You started hearing stories early on about his work ethic, just hitting balls and getting pitched to and just hitting and hitting and hitting. How he became a pro and all that stuff, it was really inspiring at a young age. I started going to games. We’d go to Boston and go to Yankee Stadium, and I was lucky enough to be around the locker room sometimes and see some of the Red Sox greats.”

He played baseball until eighth grade, then switched to soccer full-time.

“We loved baseball. Baseball was everything,” Berhalter said. “Growing up in Northern Jersey, soccer was there. We had the Cosmos, and at an early age I kind of pivoted. [Carl] retired when I was younger so [he wasn’t playing] like in those formative years when you really get into it. Soccer eventually took over.

“As you start developing you have these pathways. The soccer pathway opened up for me. My town wasn’t a huge baseball town. I played in rec leagues and stuff like that, but I never really branched out into travel, and in soccer I did really quickly. Then you just get on this track where you get to a high level and you have to invest more time.”

Berhalter played at North Carolina then turned pro in 1994, when he signed with PEC Zwolle in the Netherlands. He spent the next 15 seasons in Europe. Unfortunately, that time abroad made it far less likely that Yastrzemski would ever see his godson play. Their interaction following his 1983 retirement from the Red Sox usually occurred at Yastrzemski’s offseason home in Florida, where the Berhalters would occasionally visit. A lasting memory for Gregg is going deep-sea fishing with his grandfather and his older brother, former U.S. Soccer executive Jay. After battling a sailfish, Gregg became so seasick that Yastrzemski had to take the boat back to shore.

“Me and my brother were both green,” Berhalter said. Yastrzemski was fine, of course.

The pair hasn’t been in touch since Berhalter was appointed national team coach in late 2018. Yastrzemski, Sports Illustrated's 1967 Sportsperson of the Year, is now 80 and in Florida full-time. But Mike, 29, said he’s becoming more interested in learning about Berhalter’s life and career as his own has progressed, and as he’s developed more of an appreciation for soccer.

“I played a little growing up, but then I got away from it with baseball and am actually getting more back into it now that it’s so much more prevalent,” Mike Yastrzemski said from his offseason home in Nashville.

He said the age difference between him and Berhalter, not to mention the latter’s years in Europe, kept interaction to a minimum. There were closer connections to Berhalter’s family when Mike was younger.

“You kind of lose track of family to an extent, once everything gets to a larger scale. But I think it would be really great to sit down and reminisce, because obviously there are a ton of similarities in our past, and the mentality of being competitors, and I would love to gain some perspective from it,” Mike Yastrzemski said.

They came close to having that opportunity last year in Baltimore. Berhalter and the USA were training nearby at the U.S. Naval Academy, and Yastrzemski’s Giants were in town for a three-game series against the Orioles. But they never connected. It was shortly after Yastrzemski was called up from the minors, and he said the weekend was a “whirlwind” of family and media. A few U.S. players and staffers attended a game though, and one passed a commemorative national team coin on to Mike. He said he keeps it in a dresser in his bedroom.

“I would love to meet up at some point, once all this [coronavirus] stuff is all over,” Mike said.

When it happens, that’ll bring one of the more interestingly random family connections in American sports full circle.

Meanwhile, Berhalter is waiting for an opportunity to return to the field. The USA’s next scheduled games are in September, when 2022 World Cup qualifying is supposed to begin. But whether those matches, or any matches, take place at that point is unknown. He’s still on the job though, keeping in regular touch with the player pool and working on ways to keep them fit and engaged.

“We’re still active, still analyzing games furiously and breaking it down. It’s been fun from that side of it,” he said.

From the start, Berhalter has seemed like the sort of guy who likes to stay busy. That’s something he probably learned at an early age from his godfather.

“You learn what it takes,” he said. “You don’t play baseball for 23 years without having a really strong work ethic. I played for 18 years, and that stuff rubs off. You just go. You understand what it takes to be successful and you just try to sustain that. Hearing stories from a young age already set that tone.”

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.