His savvy on a board earned him trophies. His burglary of New York's Natural History museum earned him headlines. And his brutality on a boat 50-odd years ago earned him a lifetime in prison. Now, what does penance get you?

As Terry Rae Frank slipped under the brackish water, her brain begged her body to breathe. Part of her skull had been split open, her abdomen slit. A wire, lashed around her neck and tethered to a concrete block, tugged the 23-year-old down to a silty creek bed. And still her nervous system commanded her lungs to heave in a spasmic search for oxygen. Agonal respiration, physicians call it. As in agony. A dying body’s desperate final act.

Frank and her friend Annelie Mohn, 21, had been motoring along South Florida’s Intracoastal Waterway when their heads were battered with an oar, Mohn’s body pierced by a bullet and their stomachs eviscerated with a blade so their corpses wouldn’t rise to the surface as they decomposed in Whiskey Creek, just south of Fort Lauderdale, where the mangrove thickets once concealed bootleggers.

Those two young women reached their gruesome end after absconding in November 1967 with nearly $500,000 worth of stocks and bonds (almost $4 million in 2020 dollars) stolen from the Los Angeles brokerage firm where they worked as secretaries. A few weeks later they hopped on a 22-foot sport boat alongside the hardened men with whom they had plotted to turn that paper into profit. But as they cruised in the sunshine the conversation soured, and one of the women threatened to expose the whole scheme if she didn’t get a larger cut. Seconds later, the bludgeoning began. Agonal breaths ensued.

The women’s bodies were discarded, left to decay in the dark, sap-stained stream.

* * *

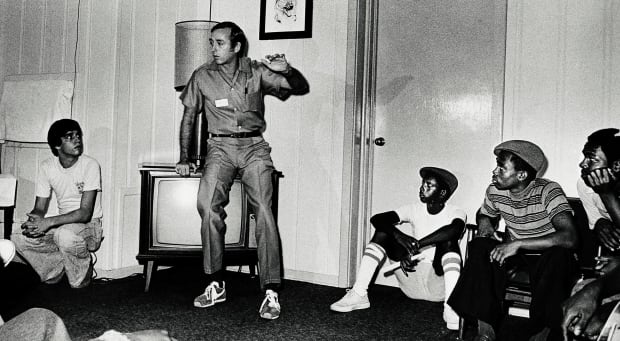

Fifty-two years later, a fit, smooth-skinned octogenarian shuffles through a small gray guard house, past a metal detector, then down a flight of stairs and past the outer wall of Hancock State Prison, a close-security facility in eastern Georgia that smartphones tend to struggle to locate. White hair slicked to the side, goatee trimmed at tidy right angles, the old man’s crystalline hazel eyes dart back and forth as if they can see around corners. A dozen volunteers follow him through electronically secured checkpoints, past row after row of razor-wire fencing that keeps prisoners, many carrying life sentences, disconnected from the world outside.

Over the next eight sweltering hours in July the man will wield his considerable charisma and intellect to help these incarcerated people reestablish some measure of that connection. They have matching white jumpsuits, orange Crocs and vacant eyes, which he stares into squarely as he shakes hands, summoning a sense of humanity, trying to conjure hope from hopelessness. Over the past 33 years he says he has done this difficult work (in Jesus’s name, for little or no money) in more than 2,000 prisons, across 45 states and a dozen countries. He first volunteered at a prison shortly after he himself was freed from one, in 1986, having spent two decades inside forlorn facilities like Hancock. He served that time because a jury convicted him and another man of compelling those final agonizing breaths out of Terry Rae Frank and sending her to the bottom of Whiskey Creek with a concrete anchor around her neck. First-degree murder. (After that sentencing, no one was ever tried for Mohn’s death.)

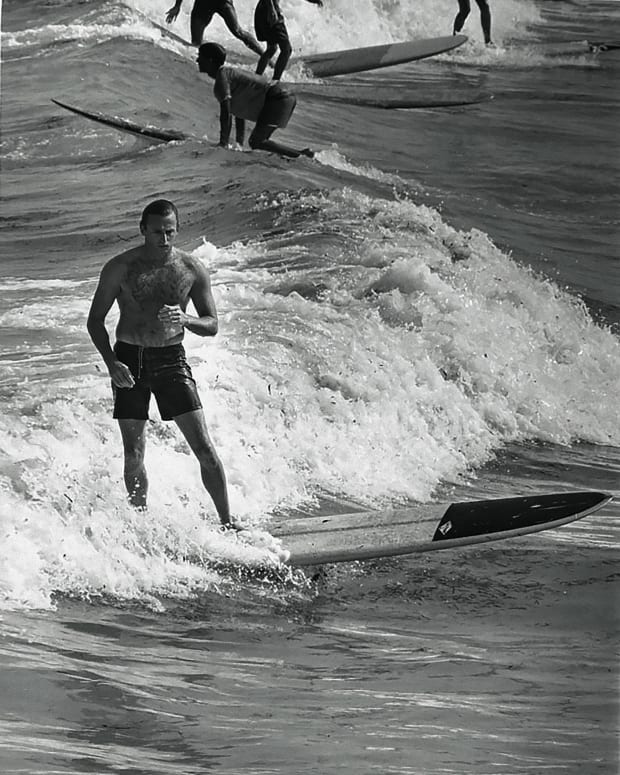

The old man’s name is Jack Roland Murphy, better known in 1960s headlines as Murph the Surf (though he always preferred Murf). As a sunglasses-and-swimsuit-wearing, bronze-bodied daredevil he won a slew of competitions—enough to be included in the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame’s inaugural class—while in his spare time participating in brazen robberies of increasing violence. His infamy peaked in ’64 when he and two accomplices broke into the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and stole $3 million worth of precious stones (in today’s dollars). That jewel heist remains one of the largest ever in the U.S., and it has long been the wellspring of Murph the Surf’s mythology. The murders, meanwhile, are routinely rendered a footnote, or disregarded altogether. In news accounts. In his own book. In the eyes of the legions of people who love him.

The streamlined legend of Murph the Surf has long overshadowed the nuanced conundrum at Jack Roland Murphy’s core: Are decades spent sacrificing for others enough to atone for a few moments of savagery on Whiskey Creek? The young man was convicted of murder. The old man brings his conviction to prison, delivers light to the darkest places, perhaps in the name of paying off an endless debt. “It’s a nightmare,” he says of the slayings. “I remember everything.”

The justice system has forgiven Murphy. As far as he is concerned, his God has too. Friends and family look past the young man’s crimes, focused on the old man’s deeds. Can you? Should you?

“Here’s a guy who was a maniac—an egotistical, narcissistic, self-serving human being,” says longtime friend and filmmaker Domenic Fusco. “If you believe, ‘If you have bad blood, you have bad blood, and that’s it,’ then you look at Jack as an actor.

“But if you’re a believer, you look at him as a minister.”

* * *

Jack Murphy’s criminal life began innocently enough: He broke into his Carlsbad, Calif., elementary school to indulge in ice cream. John Penrod, a childhood friend, theorizes that Murphy’s tense household—particularly the demands of his father, also named Jack, a stern electrical lineman—led the boy to rebel. Penrod, 80, says he once saw the elder Murphy slap his son across the face for the sin of washing dishes too slowly.

An only child in a home that demanded excellence, Murphy became an adept violinist and tennis player by his teens, finding time in between to drag 60-pound redwood surfboards down to the Pacific Ocean with his friends. He also began to count telephone poles and houses and cars on his walks home from school, sharpening what would become an extraordinary ability to case a room.

The family moved to Western Pennsylvania when Murphy was a senior in high school, and the talented teen captured the region’s singles tennis championship, earning a scholarship to Pittsburgh. “Very talented,” says Penrod. “Anything he got a hand on, he accomplished.”

If only he’d stuck to those pursuits. In 1955, longing for the sunshine and waves to which he’d grown accustomed, Murphy left Pitt after a few months and hitchhiked to Miami Beach. There he found work teaching swimming, scuba, tennis and dancing at cabana clubs and resorts. He put his athleticism to use as a lifeguard and in a traveling high-dive stunt troupe, where he did flips and twists off towering platforms. He charmed an older woman poolside one day, met and married her daughter, Gloria Sostock, and had two boys, Shawn and Michael. The marriage was short-lived, though, and Sostock took the boys to Illinois, where they would grow up moving between townhomes, with only a vague sense of their father’s identity.

Murphy, meanwhile, settled in Cocoa Beach, where he opened a custom surfboard shop and spent his free hours partying and sharpening the dexterity that would serve him well elsewhere. He’d load up a friend’s fishing boat with beer and women, then hop on his board and wake-surf behind the party for hours. When storms chased lesser surfers out of the water, Murphy rushed in to catch waves like the ones he had grown accustomed to out West. For these exploits, he earned his nickname.

Murph the Surf would go on to win Florida’s state contest in 1962 and ’63, with reports noting his nimble footwork on the board and his skill in shifting directions while carving through waves. One Christmas he delighted an Indialantic, Fla., crowd of thousands by paddling into 14-foot swells in a Santa costume. Half a century later he tends to punctuate such stories with “bro,” elongating vowels in his retellings like a 20-something beach bum.

While official records of his feats are relatively scarce, Murphy rattles off his triumphs with gusto, insisting he was never bested in competition. He says he won events in Virginia Beach, Jacksonville and Ormond Beach, Fla., where waves crashed over nearby fishing piers as a hurricane churned offshore.

Surfing, though, wouldn’t take off as a semilucrative professional sport until the 1970s. After four years in Cocoa Beach, cut short by bad business deals and a failed second marriage, Murphy shuttered the surf shop and returned to Miami Beach. There, he met Allan Kuhn. A diving and swimming instructor by day, Kuhn funded a playboy’s lifestyle with schemes like the one into which Murphy stepped in the early 1960s. The two men would plunder valuable artwork—once from the underbelly of a Greyhound bus, Murphy recalls—but instead of selling their haul they would contact the company that had insured the art, essentially holding the pieces hostage. If one was covered for $200,000, Murphy says he’d ask the insurer for $70,000, saving them a full payment to their client. “It was the easiest thing in the world,” he says.

Murphy used the photographic memory he’d honed as a child to scope out and appraise jewels worn by tourists and socialites at bars, clubs and resorts. Then, he says, he’d join Kuhn and a crew in climbing the balconies of high-rise apartments to access the loot, escaping on speedboats into Miami’s network of waterways. Once, to evade police after using a boat to rob a mansion on an island, Murphy plunged into the Biscayne Bay with a satchel of jewels and employed his swimming prowess—no different than attacking a big wave—to reach a waiting getaway car.

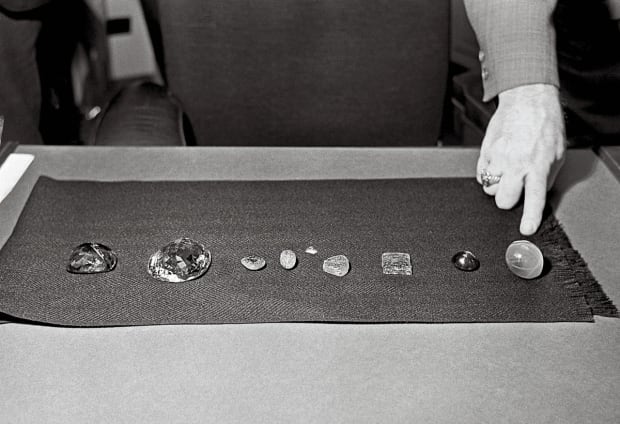

Murphy was hooked by the challenge of solving the puzzle each job presented, but the degeneracy cost him. In short order, relative fame turned to infamy. In the fall of 1964, Murphy and Kuhn pointed a Cadillac convertible toward New York City, stopping in South Carolina, he says, to knock off a jewelry store, riddling a police car with bullets as they barreled away. In Manhattan they set up shop in a penthouse apartment on 86th Street, smoked weed and snorted coke. There they plotted the museum heist, which they pulled off on Oct. 29, Murphy using a surfer’s balance to scale walls and tiptoe along a fifth-story ledge. In all, they pilfered roughly two dozen jewels, including the 563-carat Star of India Sapphire (the world’s largest), the DeLong Star Ruby and the Eagle Diamond. Later, a hotel bellhop tipped police off to their erratic behavior. Authorities raided a room laden with evidence but absent the jewels and the robbers; they eventually caught up with Murphy in Miami. At a subsequent court appearance he joked to reporters that the inconvenience of the whole thing was ruining his plans to catch some waves in Hawaii.

After a burglary conviction and then 21 months spent combating the drabness of Rikers Island—the walls, clothes and food, all varying shades of gray-—Murphy emerged in 1967, bouncing between Florida and California. By then, the sheen of the outlaw surfer was wearing off, revealing something edgier. Without divulging specifics, he claims in the subsequent years to have been involved in or privy to extreme violence and other murders, including Boston gang wars that left more than 60 people dead. “I lived in the jungle, baby,” he says.

It was into this jungle, Murphy claims, that Kuhn steered Terry Rae Frank and Annelie Mohn. At trial in Fort Lauderdale, evidence hinted that Murphy himself may have conspired with the women to steal the stocks, but he disputes that. Further, he now alleges that a mysterious third man—whom he won’t name—joined him and codefendant Jack Griffith on that December 1967 boat ride along the Intracoastal. Yet, none of the case’s 200-plus witnesses pointed to an extra passenger, and decades after the trial Murphy’s own defense attorney denied having ever heard mention of another assailant. (Kuhn was later convicted of conspiring to receive and transport stolen securities, but he wasn’t implicated in the murders.)

Here, Murphy’s account diverges far from the case the prosecution would later present: He insists he was merely piloting the boat when the mystery third man lashed out at the women’s threats to blab to the feds. “In my crowd that’s not something you’re going to talk about,” Murphy says. “Ten seconds later, I had dead people in that boat.”

Typically a fast speaker, adept at wresting control of conversations, his tenor changes when pressed on the events of Dec. 8, 1967. Murphy’s voice drops low and he pauses as he sifts through ghastly images and addresses his remorse. It was some 35 years ago that Griffith (now deceased) claimed through his lawyer that he was a mere bystander in Whiskey Creek and Murphy delivered the fatal blows. Murphy insists that’s not true. He’s careful to take blame for his role without framing himself as a full villain. He admits to hurriedly steering the blood-soaked vessel to cover, sidling it up to a construction site where he says he picked up the concrete blocks used to sink two women.

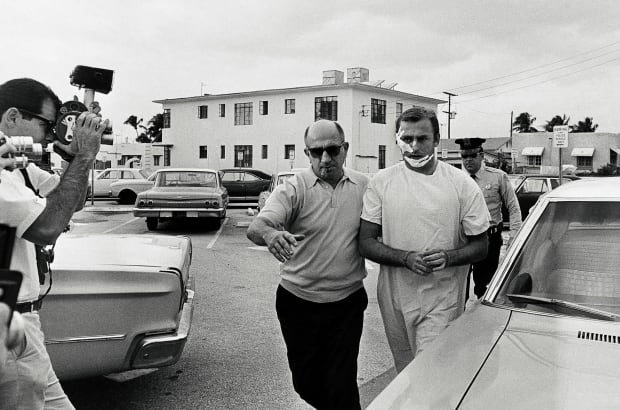

Despite those crudely constructed anchors, and the incisions across the women’s torsos, the first of the two bodies surfaced the same day they were slid into the water. It took the state five months to build a case and arrest Murphy and Griffith. In the meantime, Murphy and a crew attempted to rob Miami Beach socialite Olive Wofford in early 1968. They broke in and tried to burgle an upstairs safe, threatening to pour boiling water on Wofford’s young niece if she didn’t unlock it. But they triggered a silent alarm and Murphy, the lookout, saw the cavalry headed toward the mansion.

“High noon,” Murphy says in painting the scene some 50 years later. In the ensuing gunfight he fired his .45 at a cadre of cops, dived out a set of French doors and sliced his face open. But it was all over, in so many ways. At the police station Murphy heard cops—with whom he’d previously crossed paths—cheering the local legend’s arrest. As he was being hauled away, Murphy turned to the men in uniform and vowed to finish what he’d started. “Stay ready,” he hissed.

“My goofy beach boy cover was blown,” he says today. “Now they knew: He’ll pull the trigger.”

At one point during the ensuing jury trial for Frank’s murder, Murphy was declared “insane.” It was a ruse he says he played along with at his lawyer’s behest—until a judge ruled he was fit to stand trial. And on March 1, 1969, a jury convicted Murphy of first-degree murder, earning him a life sentence. (Griffith, who was tried with Murphy, got 45 years for second-degree murder.) In the end, the panel of 12 Broward County residents, no doubt familiar with the local celebrity’s exploits, recommended that the judge spare Murph a trip to the state’s overworked electric chair.

One year later another judge tacked on a second life sentence for the attempted Wofford robbery. Murphy (who lost an appeal to the Supreme Court) resigned himself to perishing in prison.

* * *

Before addressing the prisoners at Hancock, Murphy joins a dozen other volunteers in the gymnasium, and they hold hands in a prayer circle. The old man’s eyes remain shut, his head bowed, as a pastor offers gratitude to God.

Eventually 100-odd prisoners stream in, shaking hands vigorously with the volunteers before sitting cross-legged on a basketball court in front of a small stage. It is to this crowd—men carrying wide grins, thankful for a moment of being treated as equals—that Murphy, from a small stage in the corner of the gym, unspools the story of his incarceration and eventual salvation, the change in his beliefs that engendered mercy for a lifelong criminal whom one judge deemed unworthy to “ever again be in a free world.”

At the beginning of his sentence, at Florida State Prison in Starke, Murphy says he ran a gambling operation. He smuggled in drugs and spent seven months in death-row isolation for triggering a riot. (Prison officials, citing outdated records, were not able to confirm these details.) He got through the most mentally taxing stretches, alone in his cell, by meditating. And by dropping acid. At rock bottom, Murphy recalls, he was approached by Louie Wainwright, Florida’s secretary of the division of corrections, who admonished him for not having used his considerable abilities for good. Here was a man, Wainwright saw, with substantial clout among his fellow residents—couldn’t he use that to benefit others?

Murphy’s voice, having shifted from its usual Southern-surfer twang to a decidedly more urban one in front of a mostly black prison audience, rises here as he reaches his story’s inflection point. In 1974, Cowboys quarterback Roger Staubach and then-retired Browns defensive lineman Bill Glass visited Starke. Glass, who in his many prison visits had yet to meet an inmate with alligator loafers, was struck by Murphy’s intellect and bravado. Eventually Staubach tossed a football around with the residents, and Glass gave a speech about how salvation—forgiveness, even—lies within the Bible.

And this time, Murphy says, the message landed. Pining to feel something other than despair, or merely desperate to find a path that led outside the razor wire, his lifelong skepticism of religion began to erode. His behavior, he says, changed accordingly. He gradually weaned himself off drugs (kicking weed was the toughest) and, at Wainwright’s urging, embraced reform programs. When businessmen and religious leaders visited the prison to discuss how faith shaped their success, Murphy made sure to attend and engage. And he spent as much time as possible at the chapel, using his status—“he was the top of the rock,” says Bernie DeCastro, who served time with Murphy in the 1970s—to mentor and influence his peers, even teaching some how to read.

Whether Murphy’s personal overhaul was authentic or more like a new skin he’d slipped into, the result was, for him, a net positive. Wainwright wielded considerable influence, and in 1982 the state’s parole and probation commission bumped his star pupil’s parole eligibility date up to ’90. (Wainwright declined to comment for this story.) Two years later Murphy moved to a work-release prison ministry program in Orlando. Finally, on Oct. 22, 1986, after poring over hundreds of letters in support of Murphy, the commission voted 5–2 for release. No one at the hearing spoke in opposition.

Ultimately, Murphy was discharged on the condition that he never return to Broward or Dade counties. For the grotesqueries of Terry Rae Frank’s killing, Murph the Surf served just 19 years.

At Hancock this story gives hope, perhaps misplaced, to an audience of violent offenders, the majority of them lacking the capacity, the renown or the good fortune to navigate the criminal justice system as deftly as the teller did. After sharing, Murphy strides offstage and the prisoners swarm him like a celebrity, each yearning to catch his eye and thank him. For more than an hour he shakes their hands and touches their shoulders and listens as they articulate how they’ve changed. One mentions having read Murphy’s 96-page book, Jewels for the Journey, which covers his crimes and his jailhouse salvation but skips the Whiskey Creek murders entirely.

Another, just shy of 70, with a sinewy frame and near-concave cheeks, tells Murphy they’ve met before, in another state prison, back in the ’80s. The man has served 36 years on a murder charge—a drug deal gone sideways—but he derives optimism from today’s tale, as well as a certainty that he, too, will soon leave behind the drab walls and high fences. He insists that this belief keeps him from giving in to the misery of a forgotten man in a desolate place. “We’ve lost things we cherished,” he says. “Everybody in here is in pain.”

* * *

When Jack Murphy’s two sons eventually learned about their father’s identity, in 1972, they began an annual pilgrimage, from Illinois to whatever Florida prison was holding him each year. Michael, now 60, admits he carried some resentment into that first conversation, but he was eager to finally meet him. From that moment on, he says, he loved his dad unequivocally. He was elated, certain there would be no backslide, whenever Jack finally walked out a free man.

Not everyone felt the same. Emery Zerick, a retired Miami Beach detective who encountered Murphy as he marauded through the city in the ’60s, said upon the man’s release that he would shoot him on sight if their paths ever crossed. Murphy had been ordered as part of his reentry to pay $2,500 in restitution to Frank’s family, which they refused to accept. “What does money have to do with life?” Frank’s indignant father, Lewis Kent, told the Sun Sentinel in 1986. “[It’s] blood money. . . . In a few years, he’ll be back in prison again. He’ll get what he deserves.”

Unfazed by the criticism, shrugging off any suggestions that his newfound faith was another con from a deft conman, Murphy assured reporters he would devote the rest of his life to the work that God demanded of him. He had maintained contact with Glass since their 1974 prison encounter, and he accepted a position with the retired NFL player’s nonprofit ministry, Champions for Life. Murphy’s knack for connecting with inmates—one go-to tactic has him negotiating with wardens to bring motorcycles into the prison yards, luring people out of their cells—quickly propelled him up the ranks. Years later Glass remains undaunted by his friend’s dark history and impressed by his ability to relate to his audience. He recalls a visit to a prison in the South, where Murphy led a team of volunteers in lying on the facility’s floor so they could make eye contact and converse with prisoners on the other side of steel doors.

In his thousands of prison trips Murphy has ministered to detainees at San Quentin and, as Champions for Life’s old international director, at destitute prisons from Peru to Ukraine. He has talked with the nation’s most violent men, including Tex Watson, one of the assailants in the grisly Manson Family murders. (“He’s been God’s man in there,” Murphy says of Watson, who in 1969 helped brutally slay a pregnant Sharon Tate and three friends, and who years later, in prison, became an ordained minister. “There is something very strange and special about him.”) In sermons or over dinner he is quick to name-drop luminaries he has crossed paths with or worked alongside, such as NFL Hall of Famers Staubach, Fran Tarkenton and Mike Singletary. And while none of them returned requests to share thoughts on Murphy for this story, he has forged meaningful relationships with an eclectic stable of acolytes who eagerly vouch for him. Tino Wallenda, of the famous high-wire-act family; Tully Blanchard, one of professional wrestling’s Four Horsemen; and Kristi Overton Johnson, an accomplished professional water skier, all credit Murphy not only with showing them how to connect with prisoners but also with changing their lives by introducing them to a type of ministry that allows them to make a profound impact. “Jesus said in the Bible, ‘Follow me and I’ll make you fishers of men,’ ” says Blanchard. “There is no greater fishing hole than the lowest place in our society.”

And for so many in Murphy’s circle, his devotion to that calling has been a lure. His closest friends tend to see him only through the lens of his decades of prison ministry. In speaking about him they may mention the museum heist or the shootouts, but they seem incapable of acknowledging that he could have been involved in the murder of two women in the back of a boat. “I didn’t know the old Jack Murphy,” says Overton Johnson, who has welcomed him into her home and watched her children cling to the old man’s stories. “I don’t talk to him a lot about all of that, because I can’t imagine it.”

Murphy lives these days with his wife, Kitten (whom he met in prison, when she was working for a local news crew), in a modest home in Crystal River, Fla., famous for the manatees that drift through the town’s warm springs. Hindered by a balky lower back, he hops on a board only occasionally, and now he surfs boat wakes, not waves. He spends far more of his hours volunteering in local prisons and work-release centers, helping people find temporary housing, jobs, clothes. He’s been known to rise at 4 a.m. to pick up leftover food at the local Publix for some homeless people living in the woods nearby.

His Miami Beach gang, meanwhile, has been replaced by a group of elderly men who meet every Saturday morning to pray. Fusco, the filmmaker, says Murphy has turned down as much as $350,000 for his life rights; a proposed movie, the subject feared, would have glamorized his violent past and ignored the faith that reshaped him. “He’s very real,” insists Joseph Lounders, one of Murphy’s prayer group friends.

Shawn and Michael still visit. For the latter, that typically means a golf outing. Jack drives the cart and counsels his vast network of friends on a phone that never stops ringing; Michael listens in and plays. Neither is inclined, though, to probe into the past. “He’s sorry,” Michael says, loosely referring to Whiskey Creek. “We’ve moved on and he’s moved on and with all the good that he’s done, we’re proud of that. He would have done almost anything to not have done that. That’s enough.”

But is it? Murphy’s victims are voiceless. Their families long deceased, they no longer persist in memory. No one is countering the old man’s carefully crafted narrative, delivered thousands of times, earning him love and admiration and, it would seem, redemption. Yet Murphy continually soldiers into concrete-and-steel fortresses to connect with people society has forgotten. He performs this grueling work at 82, leaving at home a wife in a wheelchair. Perhaps it is a calling. Perhaps a late penance.

Death has become a constant in Murphy’s life. Surfing buddies and coconspirators alike are dropping off, including Kuhn, in 2017. Murphy has paddled out and seen their ashes dumped into the sea as he’s sat astride his board, staring at the horizon. He has delivered eulogies at funerals for men alongside whom he long ago set South Florida aflame. He laments that the words of kindness he offers are hollow, because these men didn’t admit their sins and give themselves to God before their agonal breaths. He loved them, but he worries they are damned.

What about Murph the Surf? With so little time remaining, does he carry any doubt about how he’ll be greeted at the gates he’s so certain exist?

“None,” he says. “None whatsoever.”

* * *

At Hancock State Prison, after the old man speeds through his life story, he gathers the few volunteers willing to speak to the people sealed inside the isolation wing. They trek through yet another razor-wired gate, then a cage of thick, steel horizontal bars, to another electronically locked door. A buzzer sounds, the lock clicks open and Murphy ambles into a triangular room where some 60 cells line the walls, rows stacked atop one another. Here men with behavioral issues are hidden—save for an hour respite each day—behind steel doors that obscure the life within. Each is outfitted with a six-inch-square window, reinforced by a grate that lets light drift in only through a few small holes in the metal. Several fans hum, but no air-conditioning tempers the Georgia summer.

Murphy begins to wander, peering through windows, wherein he finds motionless men perspiring in the shadows, unflinching even when a visitor beckons. “This is grim,” he says.

Occasionally, though, a set of eyes appear in the gloom. One man creeps to his door, toward Murphy’s words of encouragement. He is shirtless, with tattoos covering his torso. He has a brown stubble on his scalp, a ragged beard encompassing his jawline and eyes so sullen that they seem black. His body odor wafts through the window’s broken glass. Freddie is his name, he says, voice diminished even in the hush.

“You don’t get a lot of visitors, do you?” Murphy asks. Freddie slumps, pressing his forehead against the window grate, shaking it solemnly.

The old man asks whether he can offer a few words to God, then moves his fingers up to the metal guarding the window and beckons Freddie to do the same. They lower their heads and close their eyes. And together, fingertips grazing through gaps in the steel, they pray for salvation.

This story appears in the May 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe,

click here.Find more Sports Illustrated True Crime stories here

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.