In the wake of George Floyd's death at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, the sports world has responded, though perhaps none as loudly or visibly as the NBA.

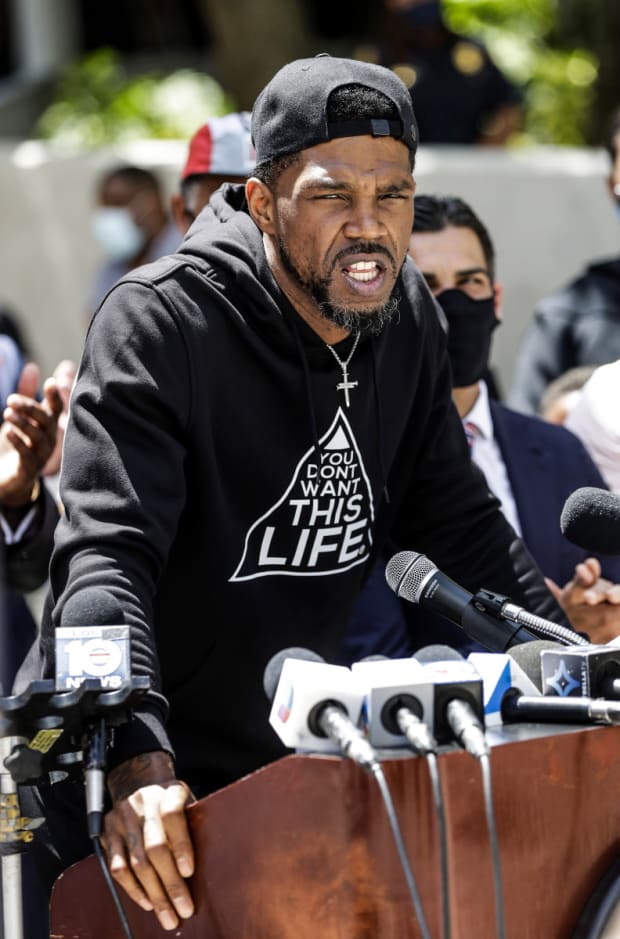

The pain brought Stephen Jackson to the steps of Minneapolis’s City Hall, the

killing of George Floyd, “my twin,” as he was known to Jackson, emboldening the 14-year NBA veteran to lead an emotionally charged press conference in Floyd’s name. It brought Jaylen Brown to Atlanta, a 15-hour drive from Boston, where the Celtics' 23-year old swingman marched through the streets, a mask on his face and an I CANT BREATHE poster in his hand. It brought Dennis Smith Jr. to Fayetteville, N.C., and Tobias Harris to Philadelphia; it fueled powerful op-eds from Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Masai Ujiri, NBA luminaries with decades of experience with racism of their own.The death of Floyd, a 46-year old father of two girls, a Minnesota transplant who for the high (alleged) crime of trying to pass on a phony $20 bill was restrained with a knee to the neck for nearly nine minutes, has sparked national outrage. Protests, some violent, some peaceful, some by people desperate to be heard, some fueled by the evilest among us simply intent on furthering the racial divide, have broken out across the country. The streets, chillingly empty for months as the nation battled the coronavirus, have been flooded, again.

The sports world has responded, though perhaps none as loudly or visibly as the NBA, a league more than 80% players of color. NBA players are routinely on the front lines of responses to social injustice, from the Miami Heat’s hooded sweatshirt team photo in the aftermath of the death of Trayvon Martin to the league-wide wearing of I CAN’T BREATHE T-shirts in the aftermath of the death of Eric Garner to this past weekend, when NBA All-Star’s like Karl-Anthony Towns, weeks removed from the tragic death of his mother from the still-raging COVID-19 pandemic, walked the streets in support of yet another senseless killing.

“I’m here because they’re not going to demean the character of George Floyd,” Jackson said. “A lot of times when police do things they know that’s wrong, the first thing they try to do is cover it up and bring up your background to make it seem like the bulls--- that they did was worth it. When was murder ever worth it?”

These are the reactions worth hearing. Forget the images of fear mongering looters and fire bombers, many of who see Floyd’s death as an opportunity to uncontrollably rage. Forget the rhetoric coming from a divisive White House, from a president whose response in the days after Floyd’s death included quoting a Miami police chief (“When the looting starts, the shooting starts”) from the 1960s widely decried for racist practices.

No, NBA voices should resonate, will resonate following tragedies like Floyd because so many of them were Floyd. “It’s funny how people think I’ve been rich all my life … I don’t deal with what they do … I don’t get racially profiled … all because I made it to the league,” tweeted Wizards guard Bradley Beal. Before LeBron James was battling Michael Jordan for GOAT status, he battled poverty in Akron, Ohio, moving a dozen times before he was nine years old, waking up many mornings wondering when his next meal would come. As a child, Beal was called the n-word coming out of gym class. In a statement, Pistons coach Dwane Casey recounted feeling helpless as an eight-year old child growing up in predominantly white rural Kentucky. Looking for something more recent? In 2018, Bucks guard Sterling Brown was arrested and Tasered for parking in a handicap space.

There’s an eagerness to assign sweeping blame in these situations. It’s the police, the officer who pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck and the three others that did nothing to stop him. But for every officer out there with no business wearing a badge, there are many that do, people who answer 911 calls and run toward danger. It’s the media, the storytellers, a belief that brought some to the steps of the CNN building in Atlanta, smashing windows and defacing and vandalizing the company logo. It’s the protesters, though each day we learn many aren’t really protesters. Minnesota officials estimated that 80% of the rioters there were from outside the state; in New York, one in seven of those arrested were from outside the city, per an NYPD analysis.

NBA players, at least the most visible ones, aren’t doing that. They are leading. Prominent WNBA players, too. In Minnesota, Jackson urged people to “make these men pay for what they've done to my brother and keep the peace.” Mystics guard Natasha Cloud encouraging, nay demanding in an op-ed for people to speak out. In San Antonio, Spurs forward Lonnie Walker scrubbing graffiti off the walls of local businesses. In Georgia, Pacers guard Malcolm Brogdon—an Atlanta native whose grandfather marched with Dr. Martin Luther King in the 60’s—told the crowd, “This is a moment.”

“I've got brothers, I've got sisters, I've got friends that are in the streets, that are out here, that haven't made it to this level, that are experiencing it, that are getting pulled over, just discrimination, day after day," Brogdon said. "Dealing with the same bulls---. This is systematic. This isn't something where we come and ... we don't have to burn down our homes. We built this city. This is the most proudly black city in the world. In the world, man. Let's take some pride in that. Let's focus our energy.”

There is no simple solution here. The country is divided, with social media and cable news siloing people off more than ever before. Leadership isn’t coming from top national officials, but local ones, like Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who urged constituents to protest when it matters—at the ballot box, in November. And it’s coming from athletes, from NBA players, who are using their platforms for good, who are urging peaceful protesting as the violence ratchets up.

“This is a peaceful protest,” Brown said in Atlanta. “Being a celebrity, being an NBA player, [doesn’t] exclude me from no conversations at all. First and foremost, I'm a black man and I'm a member of this community. We're raising awareness for some of the injustices that we've been seeing. It's not O.K.”

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.