A century ago the sports world got a new medium for conveying events with the first radio broadcast.

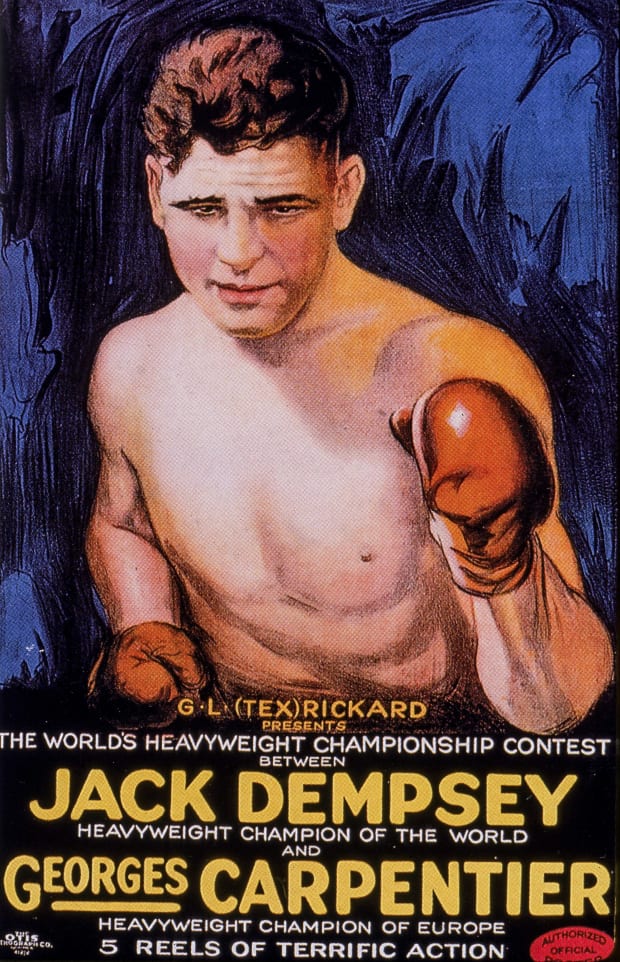

One hundred years ago Friday, on July 2, 1921, Georges Carpentier left a makeshift boxing arena in Jersey City with a broken nose, a fractured thumb and a swollen eye thanks to Jack Dempsey, who knocked him out in the fourth round of their heavyweight championship bout. Carpentier recalled shortly after the conclusion of the carnage, “I went down and out when the hardest blow I ever felt caught me over the heart.”

If anybody emerged from the bout in worse shape, it was likely J.O. Smith, who would be partially blind for several days and had burns on his hands serious enough that he had to go to the hospital.

Carpentier knew what he was getting into when he agreed to fight Dempsey, the Manassa Mauler and reigning heavyweight champ. Smith had less reason to expect to wind up under a doctor’s care, as he had a far more peaceable role: He was the first radio play-by-play man in sports history.

Like most firsts in sports, there are asterisks involved. Strictly speaking, the Dempsey-Carpentier fight wasn’t the first sporting event broadcast. A few months earlier, KDKA, a Pittsburgh radio station—the nation’s only commercial station—had aired an account of a local fight. But the technological limitations meant that the audience for the fight was miniscule group of local radio enthusiasts. The Dempsey-Carpentier bout was heard over an area of 125,000 square miles—from Maine to Maryland and as far west as Ohio—showing the viability of radio as a medium for conveying live events. As The Wireless Age, a leading industry journal of the day, put it: “Transmission of the voice by wireless on a large scale is new to the world, and the event has no little historical significance.”

The second asterisk: Smith wasn’t calling the action as he saw it ringside. He was calling it from a shack at the Lackawanna Train Station in Hoboken, two-and-a-half miles from the action.

Credit for the idea for broadcasting the fight is claimed by several men, but no matter who actually had the idea first, they all had the same motivation: to sell radios.

In 1920, radio was used for point-to-point communication. KDKA was originally established by the Westinghouse Electronic Corporation as a way for its various branch factories to communicate; anyone with a receiver (of which there weren’t many) could pick it up and before long Westinghouse realized their broadcast channel could have other uses. The technological drive at Westinghouse was led by a Pittsburgh-area engineer named Frank Conrad. In 1912—to settle a $5 bet with a friend over the accuracy of his $12 watch—he had built a receiver that allowed him to pick up time signals from the Naval Observatory in Arlington, Va. (He won the bet.)

The government rescinded civilian radio licenses during World War I, but occasionally Westinghouse’s broadcasting facilities—which were located on the second floor of Conrad’s garage—were used to test military radio equipment. (The sessions piqued the curiosity of Conrad’s neighbors, who were convinced he was a spy and reported him to the police.)

After the war, an increasing number of amateurs began to get interested in radio, after seeing firsthand or hearing about its use by the military. As more and more enthusiasts began communicating with each other, they came to a sad realization: They didn’t have a whole lot to talk about. Most of the discussions were about the broadcast—what type of equipment was being used and how clear the sound was. Conrad came up with the novel concept of content and began playing music at specified times twice a week. A year later, KDKA was granted the country’s first commercial broadcasting license so it could air the results of the 1920 presidential election between Warren Harding and James Cox. The following April, it aired that local Pittsburgh bout between Johnny Dundee and Johnny Ray.

None of this was lost on David Sarnoff, who at that time was the general manager of RCA, Westinghouse’s chief competitor in the production of radio equipment. Sometime around 1920 (the exact date, like many facts in this tale, is disputed), he crafted a memo to his bosses that began: “I have in mind a plan of development which would make radio a ‘household utility’ in the same sense as the piano or phonograph. The idea is to bring music into the house by wireless.” He went on to describe a “Radio Music Box” that would sell for around $75. He figured if 7% of America’s 15 million households bought one, that would mean $75 million for RCA—plus, he noted, “the possibilities for advertising for the Company are tremendous.”

In the spring of 1921, someone came up with the idea to branch out past music and air the Dempsey-Carpentier fight. If it wasn’t Sarnoff, it was likely Julius Hopp, a Madison Square Garden executive in charge of concerts, or J. Andrew White, the editor of The Wireless Age. No matter who had the idea, there was only one man who could make it happen: Tex Rickard.

George Lewis Rickard was equal parts Zelig and Don King. He explored the Amazon with Teddy Roosevelt. He ran a casino in the Klondike where he consorted with Jack London. When Rickard was born, according to one biography, the sounds of his first cry were drowned out by bullets flying through the cabin where his mother gave birth as a 26-man posse exchanged fire with Frank and Jesse James, whose mother lived one farm over. (Another biography, credited to Mrs. Tex Rickard, was titled Everything Happened to Him.) When Rickard died, his body lay in state at Madison Square Garden in a 2,200-pound, $15,000 bronze casket and lines of visitors stretched for 16 blocks.

But mostly Rickard, who picked up the name Tex as a lawman early in life, was a promoter. In 1920 he had signed an agreement to run the second incarnation of the Garden, which was then actually located at Madison Square. (To give himself an occupant, he formed a hockey team that paid homage to his home state: the Rangers, as in Tex’s Rangers.) But there was no way the arena could hold all the fans who were willing to pay to see Carpentier and Dempsey. So Rickard decided to construct a wood octagon across the Hudson River that would hold 90,000 people.

Rickard had a knack for ginning up interest in fights by portraying one boxer as the good guy and one as the bad. His biggest bout had been in 1910, when he notoriously cast James Jeffries as the Great White Hope against Jack Johnson, the Black heavyweight champ. Dempsey’s bout with Carpentier, a Frenchman who held the light heavyweight belt, offered a terrific storyline: war hero vs. layabout. Though in a twist, Carpentier was the former and Dempsey, who had tried to enlist but was classified 4-F, wore the black hat.

When he was presented with the idea of broadcasting the fight, Rickard was intrigued. He didn’t stand to gain financially—what little money raised by theaters charging admission to listen to the broadcast would go to the American Committee for Devastated France. But he knew the future when he saw it, so he told Hopp to make it happen.

The first order of business was to find a transmitter strong enough to pump out the signal. Hopp and White located one that had been built by RCA for the Navy. They presented a former assistant Secretary of the Navy named Franklin D. Roosevelt with a proposal: They would test his transmitter out for him. Roosevelt consented (not coincidentally, the proceeds would now be split between the committee aiding France and the Navy Club) and had the transmitter floated from Schenectady, N.Y., to Jersey.

The next challenge was figuring out where to put it. There was no structure high enough at the stadium to hold an antenna, so a plan was hatched to use the train station in Hoboken. A 400-foot tower had been erected a few years earlier. In deciding where to put the other end, White and his technicians did what Doc Brown and Marty McFly did: They ran the wire to a clock tower.

The equipment needed was sizable, and it was housed in a galvanized iron shack that the porters used to change into their uniforms. As the porters were all Black, they were not pleased about losing what little space had been designated for them. The porters assured White that they would demolish his precious tubes and switches, so White took it upon himself to sleep in the structure to guard his gear.

On fight day, White sat ringside with Harry Welker, the secretary of the National Amateur Wireless Association (NAWA). Around 1:30 the fighters entered the ring. (Both were radio fans. Carpentier was a member of NAWA, while White wrote that Dempsey was “a real amateur ham; radio is his regular evening diversion in his training periods.” Indeed, the cover of the July 1921 issue of The Wireless Age was a photo of Dempsey sitting at a transmitter.)

The crowd of 90,000 fans—including titans of business, politicians and an unprecedented number of women—roared. (The Asbury Park Press proclaimed “society and sportdom, merchant prince and shop girl, diplomat and ditch digger rub elbows in greatest fight throng.”) As the action started, White—who had practiced the nascent art of play-by-play by shadowboxing in the mirror and describing the action—relayed his descriptions over the phone to a clerk at the train station, who typed up his reports and handed them to Smith, an RCA employee and amateur radio enthusiast, who read the descriptions into the transmitter. To broadcast the action, a temporary longwave radio station, which was given the call letters WJY, was set up.

The audience consisted primarily of amateurs having small get-togethers in their homes as well as crowds who gathered at halls and theaters in the northeast to listen to the WJY signal. Some 1,200 people listened at Loew’s New York Roof in Hell’s Kitchen, while a Mr. B.D. Heller of Fordham, N.Y., who listened at his home, wrote: “Some ‘Town Crier’ I’ll say! Almost thought I was in the front row at the ringside when you counted Carpentier out. It was realistic and impressive to the highest degree.” Mr. Heller was one of many listeners to report hearing the bell. Whether that was actually possible is another mystery: One later account did assert that Smith had a small bell in the porters’ shack to recreate the ding.

In Asbury Park, a real estate salesman in a roller chair equipped with a receiver entertained boardwalk denizens by playing the fight. They had a much better time than one Casper Risley. He was listening to the fight on the third floor of his home in Atlantic City when he was struck by lightning. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported: “The instrument was shattered. Frederick Rowlman, his companion, was stunned.”

In Pittsburgh, KDKA picked up the fight. The Pirates had a home game that afternoon, and six men with megaphones relayed the action to 25,000 fans in the park. The Pittsburgh Daily Post noted that “a great yell of joy went up when it was announced that the Frenchman had the best of round three but when it was flashed that he had been knocked out in the fourth the stands almost rocked with the vibration from the throats of thousands.”

The signal was even picked up at sea. The Nieuw Amsterdam, a Holland-America liner carrying several fans to see the fight, showed up in Hoboken on July 3, the day after the fight, because of, in the words of the A.P., “poor coal.” The fans who missed the bout were at least treated to the broadcast on the ship.

One man who wasn’t upset to see the fight end was Smith. Being positioned so close to the glowing radio tubes, he was temporarily blinded for days. In the final round, one overheating tube exploded. Smith grabbed the base and pulled it out of its socket—searing his hands— before inserting a new one. As the fight ended, the transmitter was smoking and, according to an account in the 1930 book This Thing Called Broadcasting, had “resolved itself into a molten mass.”

But perhaps it had been worth it, because the book continued: “Two hundred thousand persons heard the fight.” The next month, KDKA made history with the first broadcast of a baseball game. It aired the World Series that October, as did WJZ, a Newark station that began broadcasting just four days before the Fall Classic began.

Radio had arrived as a viable medium for conveying news, and a century later, it still is—louder, clearer and, luckily for the people calling the action, safer.

• Black Belts and Fresh Faces in the Rings of Rural Georgia

• NFL Cheerleaders' Fight To Be Heard

• How Michigan Football Failed to Protect One of Its Own From Sexual Assault

• Phillip Adams Took Six Lives, and Then His Own. How Many More Were Ruined?

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.