From the Fridge to the Funky Chicken, Liverpool-born Roger Bennett—one half of Men In Blazers—was raised with an unnatural adoration of the football played across the pond.

From the book

REBORN IN THE USA: An Englishman's Love Letter to His Chosen Home by Roger Bennett. Copyright © 2021 by In Loving Memory of the Recent Past 2 Inc. From Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.Sunday nights in 1980s Britain were the loneliest nights of all. The nation still took its day of rest very seriously. Stores were closed. No professional sports were scheduled. Sundays felt like a vast, barren landscape that British television did little to enliven. Its meager offering of just three channels reinforced the somber mood, unleashing a battery of church broadcasts filled with hymn singing and pious sermonizing as well as the occasional moldy antiques road show. As anesthetizing as that mix was, it did little to divert the mind from the prospect of the looming return to school.

Imagine the thrill in 1982 when a maverick start-up network, imaginatively calling itself Channel 4, launched a weekly NFL highlight show on Sunday nights. Britain was suddenly introduced to a sporting spectacle we had no previous knowledge of in the form of an hour-long broadcast crushing highlights of all 14 of the previous weekend’s NFL games into a single hour.

And what a bombastic hour it was: a mélange of swollen blokes in pads and helmets, crashing into each other as an American broadcaster creamed himself over the “draw plays,” “rushes,” and “fumbles” that ensued. I watched episode one in openmouthed wonder, trying to piece together the terms and rules of this mysterious, chaotic ballet that unspooled before my eyes, exhilarated by the long bombs and hits as well as the gratuitous cutaways to cheerleaders in leotards on the sidelines. All this action ran at nosebleed pace, mostly as montages set to the thumping pulsations of Bonnie Tyler’s “Holding Out for a Hero.”

The glamorous titillation and pizzazz that emanated from the NFL stood in polar opposition to the prevailing culture of English football, one gripped by a fever of hooliganism and rage. Few cities were more football crazed than Liverpool and my father and I would often drive to watch our beloved Everton Football Club play in a decaying stadium that felt mostly like a war zone. After parking on some densely packed side street, a swarm of seven- or eight-year-old local kids were guaranteed to descend upon the vehicle, shrieking “Mind us your car, mister?” which meant “Can I watch your car for you, sir?” which really meant “Give me 50 pence or else I will scrape the side of your car and snap your mirrors off.”

Buy Reborn in the USA: An Englishman's Love Letter to His Chosen Home

After coughing up a coin to defuse their threat, we would walk cautiously toward the stadium, attempting to dodge phalanxes of hooligans crashing around the streets with violence front of mind. Just as dangerous were the horse-mounted policemen who chased them. It was so common to encounter the broken bodies of fellow supporters who had been savagely beaten and left to languish on the pavement that we would simply step over them.

Those NFL broadcasts introduced us to a style of fandom that was based on an altogether more enlightened way of being. The Cleveland Browns’ “Dawg Pound” was a cheering section packed with grown men, many of whom had taken the time to handcraft enormous letter D’s and matching “fences” to wave in the air when the other team was in possession of the football. The idea of sophisticated sports fans who could pull off and even appreciate such visual puns was flabbergasting to contemplate.

Even more so the New Orleans Saints fans, a long-suffering bunch who had been fated by geography to support a woeful team coached by a man in a cowboy hat whose first name was actually “Bum.” (I was fascinated by Bum Phillips, and not just because of his first name. His whole look—blue jeans, cowboy boots and trademark white Stetson—screamed Texas-archetype-American-original. The pulpit centerpiece at his funeral was an enormous oil derrick constructed out of red and white carnations topped off with sparkling light blue letters that spelled out: “Luv Ya Bum!”)

Bum’s team lost. A lot. For English fans, the rational response to all that losing would be to knife a couple of opposing supporters to numb the pain. Instead, the Saints fans elected to embrace their hopeless team’s incompetence by turning up to games with paper bags on their head and calling themselves the ’Aints. The English sports fans I knew were angry, pent up, and tribal. Most followed their team because of the street-fighting opportunities presented. American fans showed me there could be another way, that attending sports could be about something more important: an excuse to drain light beers and consume vast quantities of sausage-based product.

That difference was just as stark on the field of play. Soccer stars of the day were not substantially dissimilar to the fans who worshipped them—an unglamorous bunch who huffed and puffed around a muddy field hell-bent on kicking something, be it ball or opponent, before retiring to the pub for a cigarette, beers and a pie. NFL players, he-men like Lawrence Taylor and Lyle Alzado, were snarling slabs of muscle and pads. These were startling athletes capable of superhuman feats. To my eyes, they were a testament to clean living and a single-minded dedication to your sport.

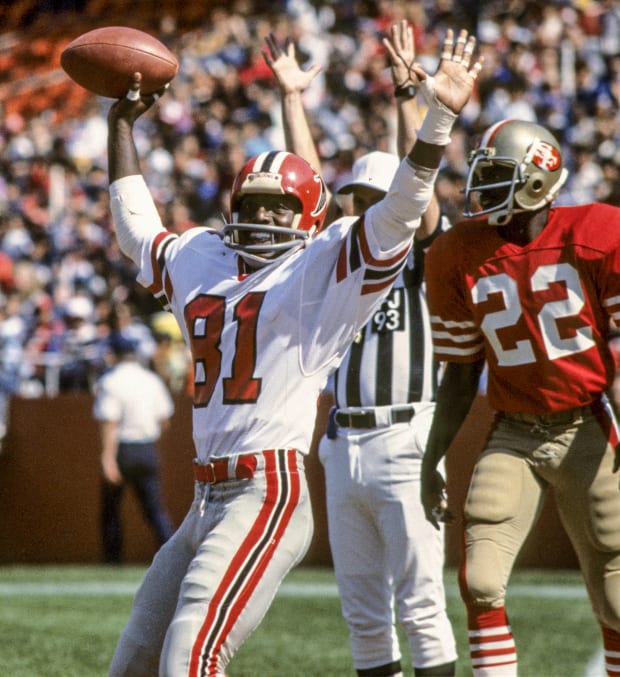

Then there was the action itself. Goals in soccer were few and far between. When an English player finally scuffed the ball into the back of the net, tradition prescribed that he should briefly hug his teammates then lollop back to the mud-filled center circle. The first time I saw Billy “White Shoes” Johnson return a kickoff was a rapturous experience. The tiny Atlanta Falcon caught the ball, duked his way through midfield and then accelerated toward the end zone, but that was just his amuse-bouche. Johnson was a player who lived less to score, more to celebrate, raising his arms in triumph while rhythmically thrusting his thighs in and out before dropping down into the splits in a giddy dance he coined “the Funky Chicken.”

I first witnessed this display of bravado-fused-with-showmanship with Jamie Glassman, my best friend, who shared an obsession with all things American. We would not have been more exhilarated if we had jammed our fingers directly into an electrical socket. The game became our everything. Jamie committed to the New York Giants of Bill Parcells, and I, because of the core belief I would have been born on the shores of Lake Michigan if only my refugee great-grandfather had stayed on the boat, developed an instant emotional connection to the Chicago Bears. And my timing could not have been better. The Bears were peaking, propelled by the free-flowing running of the legendary Walter Payton, the punk-rock tenacity of Ray-Ban-sporting quarterback Jim McMahon, and the limelight-stealing rookie lineman William Perry, a man so large he was nicknamed “the Refrigerator,” taking to the field with an effusive passion and all the naive charm of an enormous, overgrown baby.

The more we sampled, the deeper into the gridiron wormhole we both tumbled. An English monthly magazine named Touchdown landed on newsstands to service the underground market of British NFL aficionados. Jamie and I subscribed quicker than Billy “White Shoes” Johnson returned kickoffs and would spend hours poring over team rosters, memorizing the players’ positions, jersey numbers and colleges they had been drafted from, reveling in the exotic sounds of “Alcorn State” and “Southern Methodist.” The moment a new issue arrived, I would grab a pair of scissors and harvest the color photographs from the previous month’s, carefully sticking them up on my bedroom wall. Walter Payton stiff-arming a would-be tackler, the Fridge catching a pass and coach Mike Ditka chomping on a victory cigar in his signature Bears vest, now hung over my bed. I had even taken down a couple of Everton posters to make room.

A tiny classified ad in the back of Touchdown magazine introduced me to the existence of a “Tampa Bay Buccaneers UK Fan Club,” an entirely unofficial gaggle of passionate fellow enthusiasts run by Phil, a random guy who was an insurance adjuster in Brighton. I signed up after learning that the fan club’s main perk was that twice a season, Phil somehow procured an entire Buccaneers game broadcast on a VHS videotape which, crucially, had been converted so that it played on our British machines. That precious video was then circulated via mail to the fan club’s 12 members in a kind of NFL-focused underground network.

When that tape first arrived through my mailbox, the glorious thud it made upon landing was matched only by the one I experienced in my heart. Finally, I had an entire three-and-a-half-hour game at my fingertips. Detroit Lions against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, untouched by the heavy hands of Channel 4’s highlight editors, who would have stripped the game down to the mere minutes of its exclamation-point plays. It felt as if Jamie and I had taken possession of the Holy Grail. As we partook of this visual feast for the first time it was an overpowering sensory experience. The colors. The sounds. The goose bumps on our flesh.

The second the video was slammed into the top-loading VHS player, we sat back and were transported to sporting nirvana. The experience of an entire game’s ebbs and flow of play was soul-stirring, enabling us to witness moments we had never before been privy to. That coaching chess match fought out at the line of scrimmage. The trial and the errors. The two-yard runs. As great as the action was, the details of the broadcast package felt even more thrilling. A mundane 12-yard flare pass was thrillingly accentuated by the commentator screaming “Holy Moly Guacamole!” as the ball briefly spun through the air and the yellow graphics package that accompanied the replay hypnotized the eye.

Above all, though, we were mesmerized by the barrage of commercials that interrupted the game, almost inadvertently trumping the action. The advertisements we watched on that NFL video were so different from those mundane trifles that cluttered English television. American actors with their perfect teeth, Day-Glo wardrobes and aspirational joy, dizzily singing the praises of Chevy Nova Twin-Cams, space-age-looking Swatch sunglasses and Cherry Coke. It only took a single exposure to two old men named Bartles and Jaymes to make us practically ache for a new beverage called “the wine cooler.” (There was one Ford commercial featuring maverick Washington running back John Riggins that was such an earworm that I can still remember the opening lines today, even though that video was only in my possession for a single weekend. “When it comes to trucks I’m a connoisseur from the size of the engine to the sound of the door. Because I’ve been known to treat things rough, you can’t go wrong with a tough Ford truck.” Hip-hop was in its early days, but Riggo was already all over it.)

We did not watch that Buccaneers video as much as we inhaled it. By game’s end, its stunning smashmouth potency had fomented an electric energy deep within us, and we charged into Jamie’s garden to run it off. The two of us English teens made believe we were actually in Detroit, flinging a rugby ball back and forth between each other, and trying to ape the moves we had just witnessed on television. In our imaginations, Frank Gifford was commentating, screaming “Holy Moly Guacamole” as last-second Hail Marys were flung and diving catches executed. Night descended, but we kept on, continuing to perform sack dances in the darkness and attempting the “Funky Chickens” until exhaustion kicked in.

That Tampa Bay Buccaneers tape was like eating an apple from the Tree of Knowledge. Now that we had accessed an entire game and knew the real deal clocked in over the course of several riveting hours, the heavily condensed Channel 4 highlight show was entirely insufficient. Desperate times called for desperate measures. English telephones were still considered to be the centerpiece of modern home technology, yet they remained money pits if used for anything but local calls. My father studied every monthly bill with the zeal of a forensic accountant and would go berserk if one of us had even dared phone nearby Manchester. Though only 50 miles away, that call would cost a long-distance small fortune.

That price paled in comparison to the tearing ache Jamie and I experienced on Any Given Sunday. So, whenever the Bears were scheduled to play, we would carefully calculate the six-hour time difference between Illinois and Liverpool and gather around the telephone Jamie’s parents mistakenly trusted him to have in his bedroom. Yes, Jamie may have been a Giants devotee, but he was a sufficiently generous friend to cede to my fandom. With pulse pounding, I would watch him solemnly push the speakerphone button before dialing an entirely random 312-Chicago area code phone number. We would wait for the stranger to pick up at the other end and then launch right in, peppering them with questions about the Bears game they were inevitably watching. Who had possession? What down was it? How was the Bears’ vaunted pass rush looking? The goal was to hook the unwitting Chicagoan and hope they could be persuaded to give us our own personal play-by-play.

It was astonishing just how many strangers could be tempted into conversation with two kids, losing themselves for up to half an hour, transfixed, perhaps, by our English accents. We would chat about who they were watching with, what they were drinking—nine times out of ten it was Old Style, the favored beer of Chicagoans—and whether they were fans of the television show Cheers, until our ever-more-invasive line of questioning wore them out. After thanking them profusely, we would slam the receiver down, laugh out loud and go again. Another 312 number would be arbitrarily dialed, followed by a breathless wait as the thrilling sound of the single peel of that American ringtone we were so familiar with from movies rang, live and directly into our ears. The two of us huddled together, anticipating the delicious moment when the call would click in, the next unwitting Bears fan answered “Hello . . . ,” and we junior NFL anthropologists could begin anew.

• For Ohtani, and Others, an Interpreter Is So Much More Than You Think

• Phillip Adams Took Six Lives, and Then His Own. How Many More Were Ruined?

• Tragedy and Hope: A Prospect, a Scout and a Pop Fly

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.