The juggernaut squad isn't fazed by the fan-less Tokyo Olympics. In pandemic times or not, the team dominates competitions, no matter if the arena is jam-packed or full of empty seats.

Sign up for our free daily Olympics newsletter: Very Olympic Today. You'll catch up on the top stories, smaller events, things you may have missed while you were sleeping and links to the best writing from SI’s reporters on the ground in Tokyo.

TOKYO — The Tatsumi Water Polo Centre is located down the street from its more celebrated aquatic cousin, where famous swimmers race each other in the pool and Katie Ledecky mines for gold. To arrive at water polo here, the fortunate few who can enter a mostly empty stadium must ride a bus or taxi, slide past security, walk away from the swimming, navigate a byzantine maze of stairs and corridors, then climb roughly 742 flights of stairs.

This kind of exacting journey should be rewarded with a festive atmosphere, especially when considering the juggernaut known as the U.S. women’s national team is playing. They lose in international competitions about as often as America changes presidents, winning and winning and winning until the next Olympics, when one reporter or five pops over to write about their dominance.

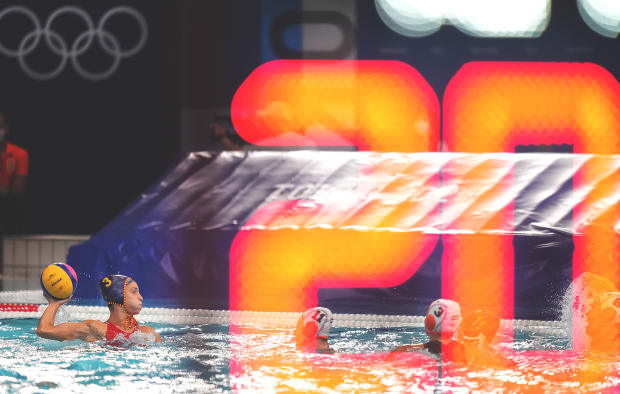

And yet, on Wednesday, silence greeted the lucky few who could wiggle their way inside to watch the U.S. take on Hungary in pool play. By unofficial count, one end of the pool featured four photographers in the stands, along with a person wearing a white polo who probably was not allowed to sit there. On the opposite side, one camera operator and another photog stood together, so close that they looked like one person. In what normally would have qualified as the nosebleed section, there was not a soul to be seen. So, three sides of the arena, one dominant team, and the unofficial attendance: six.

The final side was packed by comparison, but because it contained only journalists, volunteers, security and the sport’s officials, it could not be considered a crowd at all; or, if someone had to view those folks that way, they should consider the group the worst crowd in sports. The hacks were more likely to cheer the relatively solid selection of dining options in the press room than the action, spirited as it was, in the pool.

Now, because this Olympics took place during a pandemic, amid an extended state of emergency in Tokyo and record local highs for COVID-19 positives this week, the water polo dynasty is not alone in pursuing a gold medal without a crowd. Well, they are alone, almost, technically, even if the stands suggest the opposite. But there is an important difference between these players and the other, top American teams.

They’re used to it.

Where sprinters like Usain Bolt run as if fueled by the energy of a packed stadium and swimming races unfold in front of frenzied grandstands, the water polo players dominate international competitions under varied surrounding backdrops. Occasionally, the stands are full; mostly, they are far closer to empty, all over the world, in pandemic times or not.

It’s a shame, because the U.S. women win at a staggering rate. They feature Maggie Steffens, who should leave Japan as the all-time leading scorer in Olympic history and who still played against Hungary, despite a shiner on her left eye and a purple nose. Meanwhile, Ashleigh Johnson, the American goalkeeper, amassed the top save percentage in the last Olympics, which, of course, the U.S. won.

Same as in 2012. Same as the last six World Leagues, the last five Pan American Games and the last three World Cups. In the previous four years, this group lost three times before Wednesday and won 128 other times. One Japanese opponent, after a 25-4 drubbing here, called it an “honor” to be demolished by them.

These women project an extreme example of an Olympic misnomer: that no crowds, or severely limited ones, present something other than normal. More athletes here ply their trades in empty stadiums, arenas or parks than overstuffed ones. “The bigger sports, maybe that gives them the extra energy they need,” said Kaleigh Gilchrist, an attacker from California. “It’s different for them, I’m sure.”

The U.S. water polo players typically find their largest crowds at home. But in places like Russia, or China, they might look up at the stands and see not even a single body. They’d be lying if they said they didn’t care, didn’t wish for packed grandstands and feverish bases. But they’re not lying when they say it doesn’t matter—and that’s partly because one reason they have been so dominant is they raise their collective energy themselves. “Whether we have fans or not,” said Maddie Musselman, another attacker, “it really feels like we do.”

So there were fans at Tatsumi, beyond the journalists from Europe. They played for the same teams that clashed inside the pool. They yelled and cheered and clapped and hollered, piercing the silence with screams and chants. The noises they emitted only traveled further and sounded louder, amplified by all the empty space around them.

There were whistles that shrieked. Screams that sailed. Shouts that echoed, bouncing off the walls. The announcer droned on, all but whispering in comparison. And music, but only during breaks. The U.S. ended up dropping its first Olympic contest in 13 years, losing 10-9 to Hungary but not denting its gold medal hopes even a little bit. The women will face the team from Russia in their final pool play contest on Friday.

Regardless, players like attacker Stephania Haralabidis are not discouraged. Not with the defeat, stunning as it was—and certainly not by the lack of fans. She notes that her sport already requires mental toughness, that for all the swimming, all the grabbing and all the shooting, strategy remains a significant factor, along with the ability to recover under adverse, physical conditions. They’ll have crowds—back home, anyway; and here, from the team bench.

Musselman would advise players on teams less accustomed to swaths of unoccupied bleachers to look left or right, rather than up. The people on either side will be the ones who matter, she says, and by holding tight onto those connections, it’s easier to forget about the crowd—or the lack of one.

What’s funny, in light of all this, is one slice of how the team prepared for Tokyo. Having won 69 straight games, coach Adam Krikorian decided to get creative to keep challenging his players. So, he sent them on a seven-day silent retreat.

More Olympics Coverage:

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.