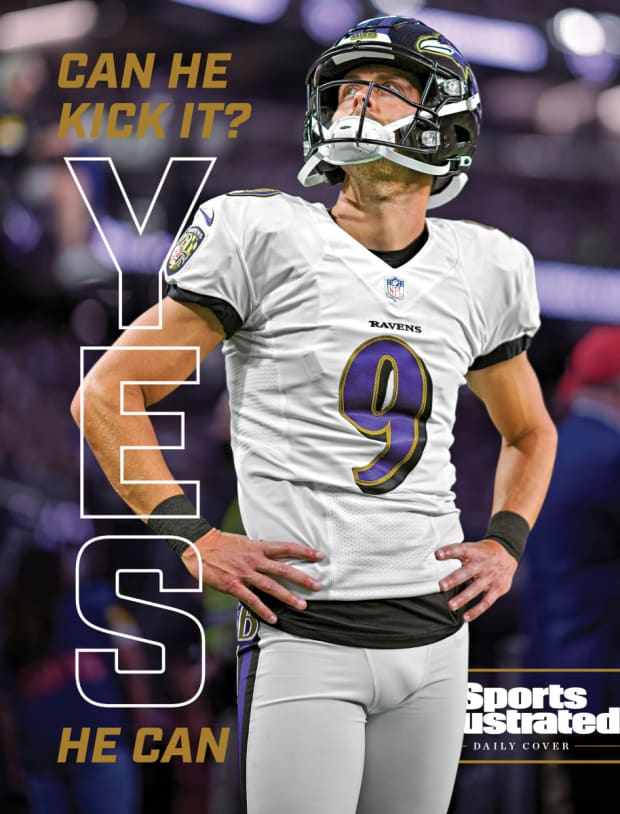

How the Ravens’ opera-singing, record-setting kicker calls on both his standout talents.

Before and after every practice, Justin Tucker rehearses. He climbs into his SUV, cranking up a playlist that covers modern rock to Italian opera and croons along for the 15-minute commute between his Baltimore-area place and the Ravens’ facility. “I guess the car is my music studio,” Tucker says. “I can get in two or three arias, including a little warmup, if I’m really feeling it.”

Tucker is typically feeling it. This was most obvious last weekend, when the NFL’s most accurate kicker ever converted his 50th straight fourth-quarter/overtime field goal in style,

belting an NFL-record 66-yarder that bounced off the crossbar and through as time expired to walk off against the Lions, 19–17. But it also applies to special teams meetings, locker room showers, and all the other impromptu venues where fellow Ravens find themselves serenaded by Tucker’s classically trained bass-baritone.Beginning in 2012 when he signed with the Ravens as an undrafted free agent out of Texas, Tucker’s larynx seemed to capture as much interest as his leg, leading to commercial appearances, charity gigs and countless articles. And while the Justin Tucker Show hasn’t made a public appearance since his runaway victory in “Most Valuable Performer,” a 2018 NFL player talent show aired on CBS—this is largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic: “The idea of trying to fill up a concert hall or a church to go sing in front of a gathering of people ... hasn’t been worth the risk,” he says—it has perhaps never been more instructive than now to view Tucker’s growing legacy as a kicker through the lens of his love for singing.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Consider the overlaps: With an 82.7% career conversion rate from 40-plus yards, also tops all-time, Tucker displays the range to hit low Cs and long FGs. Both pursuits require rhythmic precision, the sort attained through diligent, repetitive training. And while his commutes are exclusively private gigs, the audience limited to his airbags, Tucker’s song choices play vital roles in shaping his day. “If it’s first thing in the morning I can get the vibe right, a little more energized and motivated,” he says. “Then on the way home, I’ll just carry a tune to unwind.” (Plus what are uprights anyway but prongs of a giant yellow tuning fork?)

All of which has set the stage for “the best kicker in NFL history”—as Ravens coach John Harbaugh declared soon after Tucker beat the Lions, albeit with the help of a friendly crossbar—to keep making records in his second decade, no signs yet of missing a beat.

As Tucker explains, “Honing in on your craft and developing a technique that looks a certain way, time and time again—that requires much preparation and hard work. To make something that is actually difficult appear easy, I think there’s a level of artistry in that idea.”

Tucker is on the phone in early September, pondering a question after practice: What is the most nervous he’s ever been, singing or kicking? Initially his reply comes fast: “That would definitely be on the stage. The field—that’s my place; that’s where I’m in my comfort zone.” Then he reconsiders and switches course, settling on a coin toss of two nail-biting events.

One took place in the divisional playoffs of his rookie season, five months after he beat out Pro Bowler Billy Cundiff for the starting job during training camp, when Tucker jogged onto the field in Denver for a game-tying extra point with 31 seconds left, in front of a crowd of 76,732, following a 70-yard touchdown known among Ravens fans as the Mile High Miracle. “I had the butterflies going crazy in my stomach,” says Tucker, who nonetheless nailed the point-after and later booted Baltimore to the AFC championship with a 47-yarder in double overtime.

The other arrived three years later as Tucker took a deep breath before singing “Ave Maria” inside the historic Baltimore Basilica cathedral, which on that December 2015 night hosted a packed house—this crowd of about 900 Christmas concertgoers—buzzing in anticipation of the guest soloist. But again he shook off the nerves to deliver a memorable performance, and not only because he similarly nailed the aria despite having just one dress rehearsal with the orchestra and choir.

“I remember my colleague, before the concert, went back behind the Basilica to the sacristy, where the priests get dressed,” says Bill McCarthy, executive director of Catholic Charities of Baltimore, which puts on the annual event. “And there was Justin, in a tuxedo, doing push-ups. It was like, ‘Wow, he prepares like he prepares for a football game.’ ”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Tucker first took to music as a kid in Houston, starting with the trumpet in middle school. “Brass is where it’s at it,” he says. Self-taught guitar followed, as did another more percussive pursuit in eighth grade: kicking footballs. High school brought a hiatus when a stodgy band director forced Tucker to choose between his mouthpiece and his mouthguard. But he rediscovered the joy in many ways while on campus in Austin, producing a mixtape with some Longhorns teammates, successfully auditioning for the Butler School of Music and majoring in recording technologies.

Though Tucker displayed some vocal chops throughout college, his abilities crescendoed when he spent both semesters of his senior year studying under Nikita Storojev, an associate professor of voice at the University of Texas and a bass with opera credits across the globe. In particular, Tucker learned an Italian technique known as bel canto, or beautiful singing, which requires such taxing training that Storojev likens it to playing chess while also running a marathon. “You need to use your intellect and your physical potential,” Storojev says. “It’s based on muscle coordination. He had to learn how to support every note, how to concentrate, how to use his diaphragm. And if you work in sport, you’re able to use your diaphragm.”

Tucker made swift progress, impressing Storojev with his ability to sing in six foreign languages (Italian, Spanish, German, Latin, French and Czech); his rehearsal habits (“You ask him to learn something, next lesson he know the whole piece by memory,” the professor says) and his raw talent. “His natural voice has beautiful color,” Storojev adds. “It’s easy for me to teach him, because we have all kinds of similarities.” The results? “In one year, he jumped from amateur to professional level. He learned what sometimes takes people their whole life.”

A former defenseman for the Russian army hockey team in the late ’60s and early ’70s, he says, Storojev also recognized Tucker’s knack for staying cool in the spotlight. “Sometimes singers have too much emotion, and he learned from sport how to control his emotions. Once I tell him, ‘Imagine you perform in front of 10,000 people.’ Opera houses are around that. I remember his answer: ‘No problem; I perform in front of 20,000.’ ”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

The same personality trait stands out to Tucker’s closest colleague today. “The reason he’s as successful as he is,” says Sam Koch, the longtime Ravens punter and holder, “is because of his confidence and his swagger. He knows how to take the mind out of it.” A rigid routine is one way. “He warms up the same way every day, goes out there and hits the same balls every day,” Koch says. But the duo also keeps the mood light, muttering inside-joke catchphrases to each other before big kicks. Examples include Prepare For Glory and, for reasons Koch cannot explain, Babies and Memories. “Just a funny thing to ease the moment,” he says.

It is in this quest for metronomic repetition that Tucker’s two passions diverge. “A lot of guys listen to music on their headphones coming into the stadium, or in the locker room, or out on the field playing catch,” he says. “In that way, music is more distracting for me than it is helping me focus. I tend to not listen to anything around game time. I want to just dive deeply into my technique and visualize and try to get an idea for what the wind is or how the grass feels underneath my feet.”

Even so, the parallels are inescapable. (Just beware of those pesky “parallel fifths situations,” Tucker says, “which anybody in the music theory world will tell you is no bueno.”) Consider the 1.3 seconds of harmony required for every successful snap, hold and kick sequence. “The execution of our operation, all of us coming together to do our jobs,” Tucker says, “to draw upon another fine arts term, it’s like a choreographed dance that we’ve practiced time and again.”

The unit had a rare change this offseason when the Ravens parted ways with 11-year long snapper Morgan Cox and gave the gig to rookie Nick Moore. And while the old trio was guitar-string tight, vacationing together in Las Vegas after Baltimore won Super Bowl XLVII, the revamped one has picked things up no problem, with Tucker connecting on 7 of 8 field goals and 7 of 7 extra points entering Week 4. “I view our relationship like brothers,” Koch says. “Sometimes we fight; sometimes we get along really well. But we all hold each other accountable.”

Meanwhile, Tucker keeps his vocal cords fresh whenever possible. He traditionally introduces the plays of the week at Ravens special teams meetings with a football-themed jingle, Koch says, often accompanied by “some sort of Chris Berman–type additive.” He sings backup to his son in whatever 5-year-old Easton is digging that day, which lately has been the Pokémon theme song and the soundtrack to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. And he continues to squeeze in those commuting rehearsals, though he notes that he is “in less of a classical phase and more a post-’90s grunge rock vibe right now, like Third Eye Blind. So maybe it’s a ‘Semi-Charmed Life’ on the way to work and a ‘Motorcycle Drive By’ on the way home.’ ”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

With live concerts back in full swing across the country, McCarthy hopes Tucker will return for a third appearance at the Catholic Charities Christmas Festival. (In 2016, accompanied by the Morgan State University Choir and the Choral Arts Society, the kicker followed up “Ave Maria” at the Basilica by bringing down the house of worship with “O Holy Night.”) But for now McCarthy will settle for watching Tucker kick instead of sing, texting Sports Illustrated last weekend, “Maybe he did push-ups before that 66 yarder!”

More likely is that, aside from taking an extra half-hop step to generate more power, as though he were kicking off, Tucker delivered his signature moment precisely because he did nothing special. He lined up at the spot of the hold, vision fixed on the middle of the uprights. He took three steps back and two to the left, crossing his chest mid-slide as a nod to his Christian faith. Then he charged, planted and swung, and once again it was curtains at the Justin Tucker Show.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Two Generations of Gores

• Nathaniel Hackett: Neurobiologist, Hip-Hop Dancer, Your Next Head Coach

• Orlando Brown Jr.: The Son of Zeus Forges a New Path

Post a Comment

Thanks For Comment We Will Get You Back Soon.